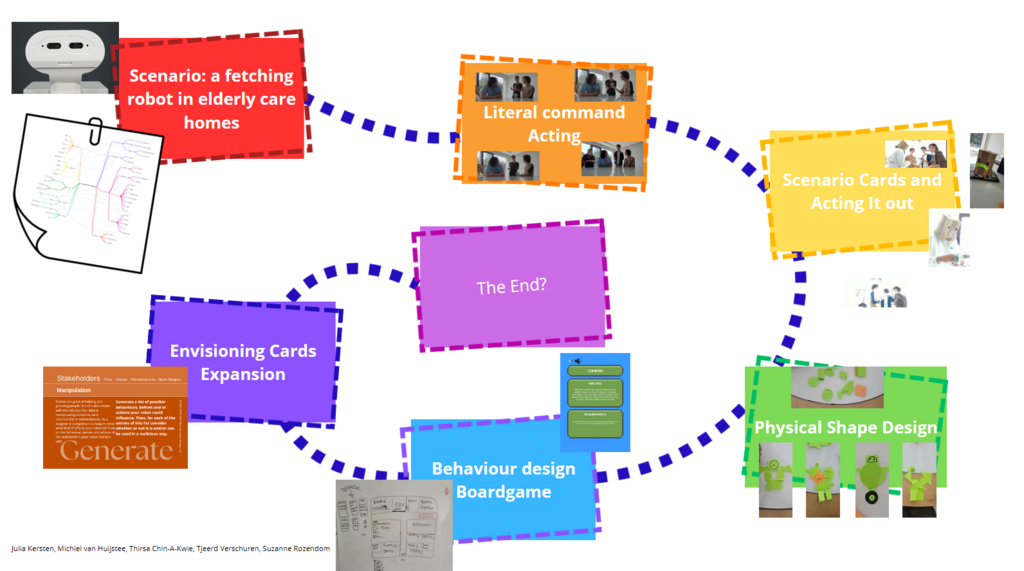

Session 1 : Deciding on a case

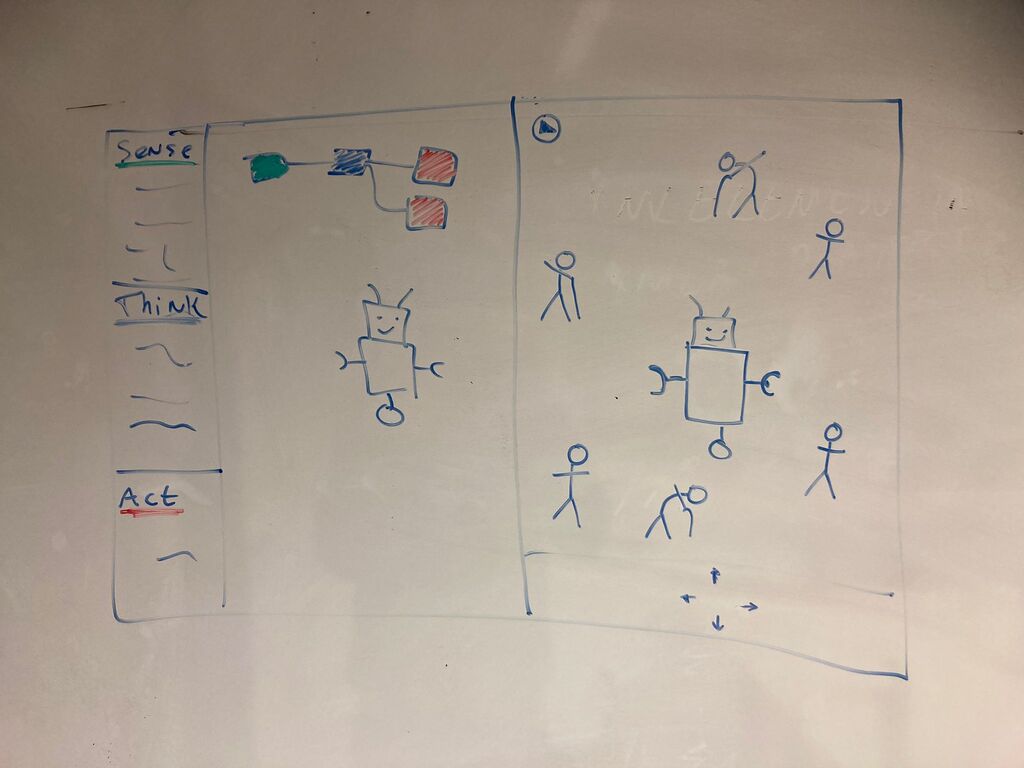

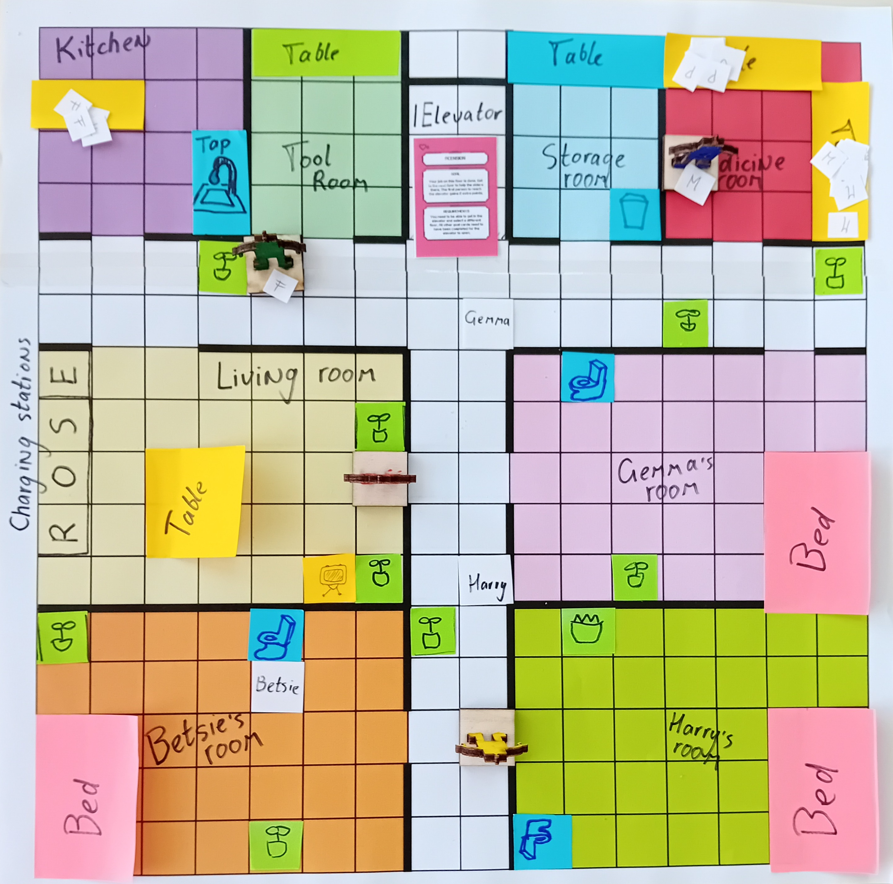

It is the start of the course Social Robot design and this week we will be deciding on a case to work with for the rest of the course. The setting is the ROSE robot (Figure 1.1) in elderly care. I formed a group with Julia Kersten, Michiel van Huijstee, Tjeerd Verschuren and Suzanne Rozendom and together we discussed possible applications for ROSE in elderly care. Possible options we came up with are: 1) Navigation and direction, 2) Measuring tasks, 3) Wayfinding, 4) Household tasks, and 5) Fetching. For these applications there are multiple things we as designers would need to address. For some applications ROSE needs to move around, so how does it move safely? How will it communicate with people it meets on the way? Other questions that need to be answered in the design could be: What needs to be measured with the elderly and how will ROSE approach this? How will it hand things over or put things down? How can Figure 1.1 ROSE robot ROSE determine what needs to be cleaned and how will it proceed to clean? What other household tasks can be done by ROSE? All these questions lead to several preliminary requirements for ROSE:

1. Must act

2. Must understand speech or other forms of communication

3. Must avoid bumping into people

4. Should move comfortably

5. Should move predictable

6. Should move smoothly

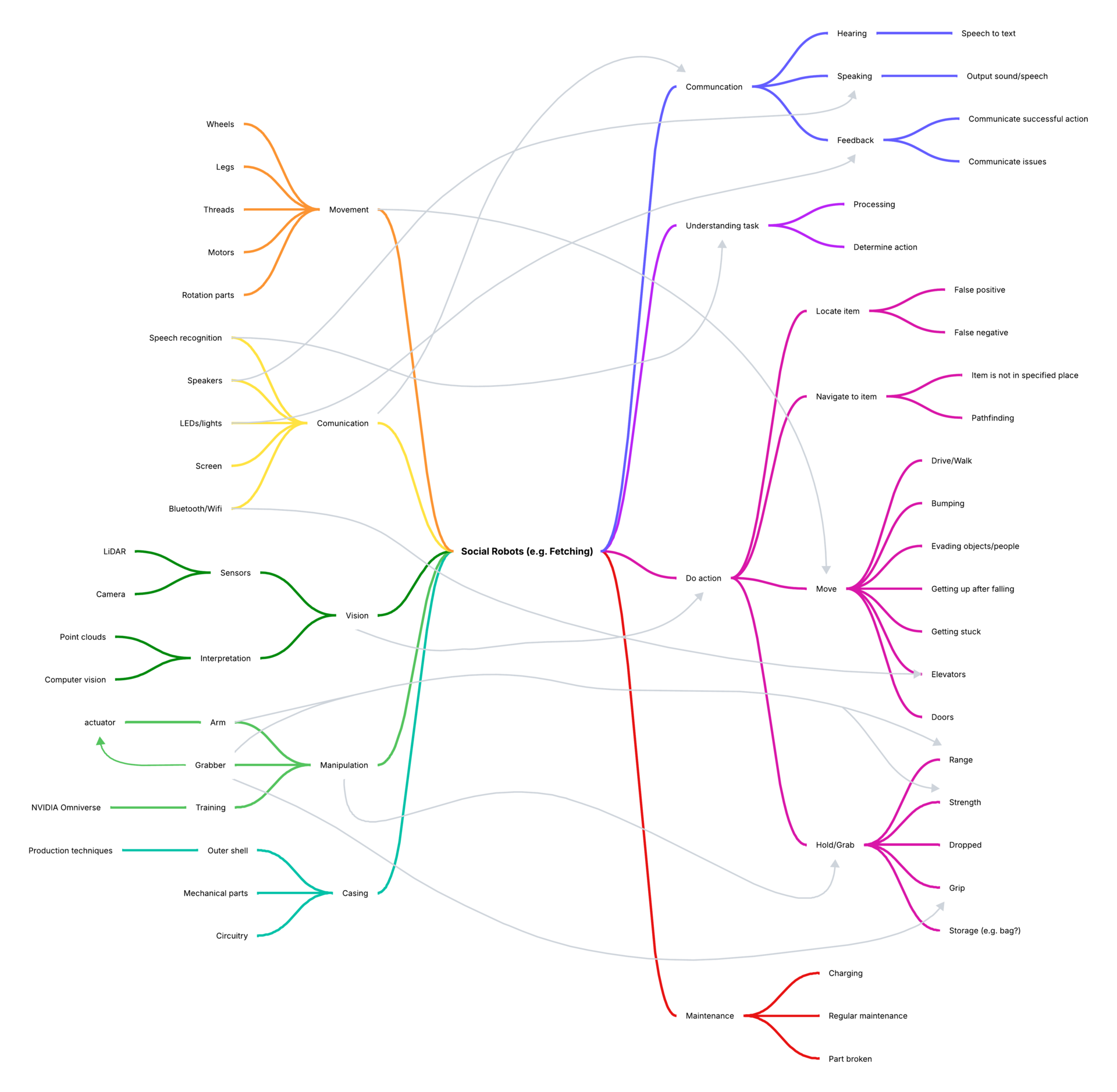

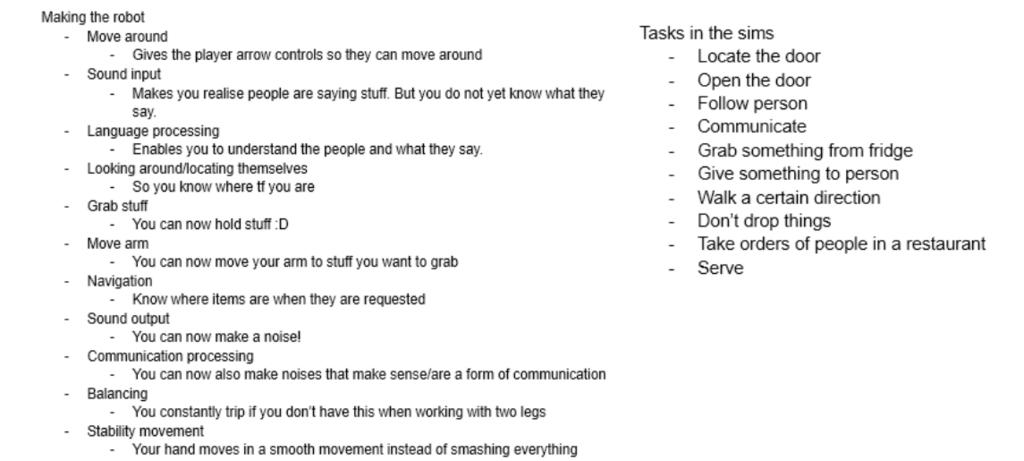

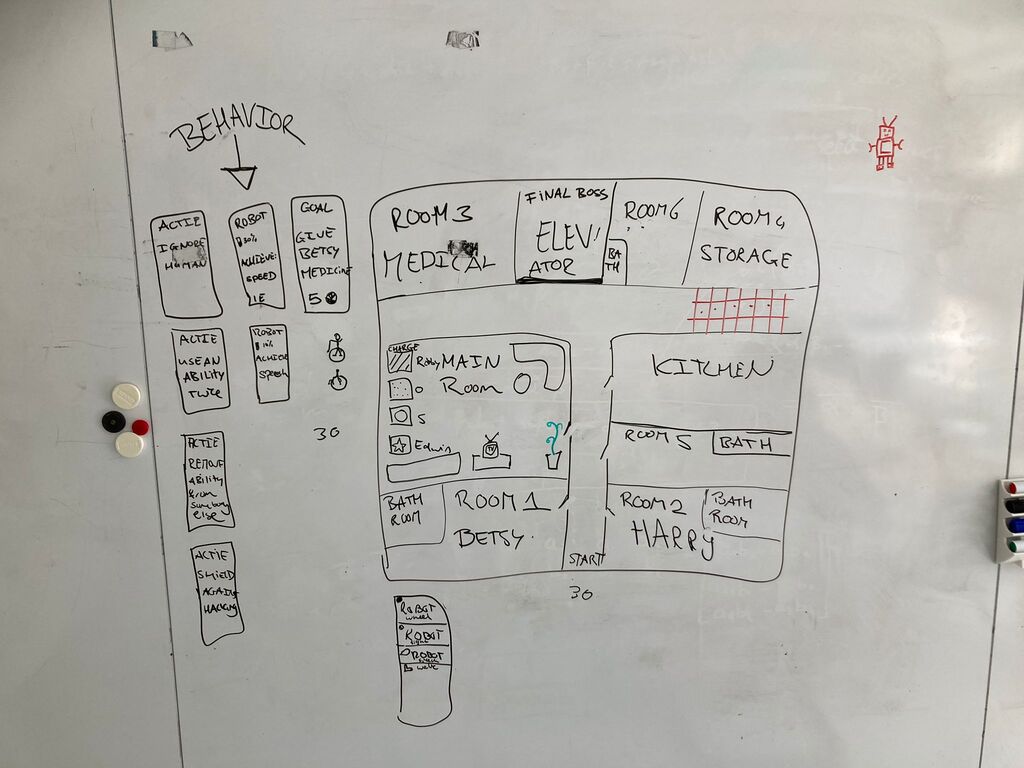

We eventually chose to work out ROSE as a fetching robot in elderly care. We started brainstorming on the problem space and created a mindmap. We expanded on this mindmap with possible building blocks and other applications. We then created links between both sides of the mindmap. The end result can be found below in Figure 1.2. Wizard of Oz could be applied to all driving and fetching, meaning that ROSE would be remote controlled to ensure it can drive around and fetch things. It can be translated into a theatrical exercise by trying to ask ROSE to fetch something and show how the interaction between ROSE and the user could proceed.